The weekend my friend Juan moved into an apartment behind the house, the police found the bodies. The smell of it still haunts him.

Most of my friends who lived near there brought up the stench. The New York Times reported that even then-Dutchess County District Attorney, William V. Grady, confirmed that it "is not your average home -- it stinks, it is garbage-ridden."

The odor of the green clapboard home at 99 Fulton Avenue in Poughkeepsie reached far enough to gag people on the sidewalk. The house was ramshackle on an otherwise idyllic middle-class street. According to The Daily News, maggots prospered in the sinks, and Kendall Francois' younger sister Kierstyn (sometimes spelled at Kirsten and Kirstyn in reports) slept on a mattress coated with their casings. It is two blocks from Vassar College. Hardly a bad neighborhood and less than a stone's throw on either side from a neighbor. One neighbor is so close that one could look from its second floor into the attic.

Francois used this squalor to his advantage, telling his family that the overpowering reek was only a dead raccoon -- which either massively overestimates raccoons or underestimates eight unembalmed dead women stored there. (He had an older and another younger sibling -- Raquel and Aubrey, respectively -- but they were not present in the home at the time of his arrest.)

Yet his family maintained the air that they were commonplace, middle-class people. His mother, Paulette, worked to help mentally ill people get jobs. Kierstyn sought a degree in family studies. The ironic overlap of their professional motivations and Kendall's crimes is aching.

I had never met Francois. I was too old (and in the wrong town) for him to be my detention and hall monitor, his job at Arlington Middle School before his tenure as a serial killer. No one mentioned him when I substitute taught there, even in whispers. The children didn't know that they learned grammar where once a serial killer earned his keep. It was only seven years after Francois -- uncreatively dubbed "The Poughkeepsie Killer" (he didn't deserve a better moniker and had been previously called "Stinky") -- had been active.

(Poughkeepsie had another serial killer the same decade, Nathaniel White, who killed six between 1991 and 1992. He does not seem to have made as much of an impact on the community.)

According to my sources, Francois tried to abuse what little power his job at the school gave him by assigning girls to extra detention and asking at least one to write him an essay explaining why she was late. Though Francois did not directly assault any of the children, students and employees of the district told The New York Times he would touch the young girl inappropriately and give them lunch detention to force them to be around him.

Francois was strange in manner but not exceptionally so. Every weekend, he played Magic: The Gathering at the local comic shop, Dragon's Den. A friend's ex boasted about having regularly played chess against him. Francois had friends, though few would admit to it after his arrest.

There is no lack of facts that chill those hearing, imagining what might have been. Years before his killing spree, Francois worked as the au pair for a child with whom my friend Liz had worked. He did nothing untoward, which is almost eerier. He kept that monster in him quiet, compartmentalizing his life. Some details lead to morbid speculation with no resolution, such as that he was unemployed during the killing because Anderson School for Autism had fired him for unstated reasons. Had he attempted to victimize one of the clients there? We cannot know.

To The New York Times, his high school teachers remembered a vocal, diligent young man who "sort of kept the class interesting." Though not a star pupil, no one mentioned seeing in him the seeds of what he would become.

My brother Dan was in Francois' classes at Dutchess Community College. Francois was loud and funny, though he fixated on any women he saw -- not in the sense of a serial killer, my brother made clear, but a serial sexual harasser. In one class, the professor jokingly asked if any students had murdered someone. Francois raised his hand, provoking laughter from the rest of the class, which must make them shift uneasily now.

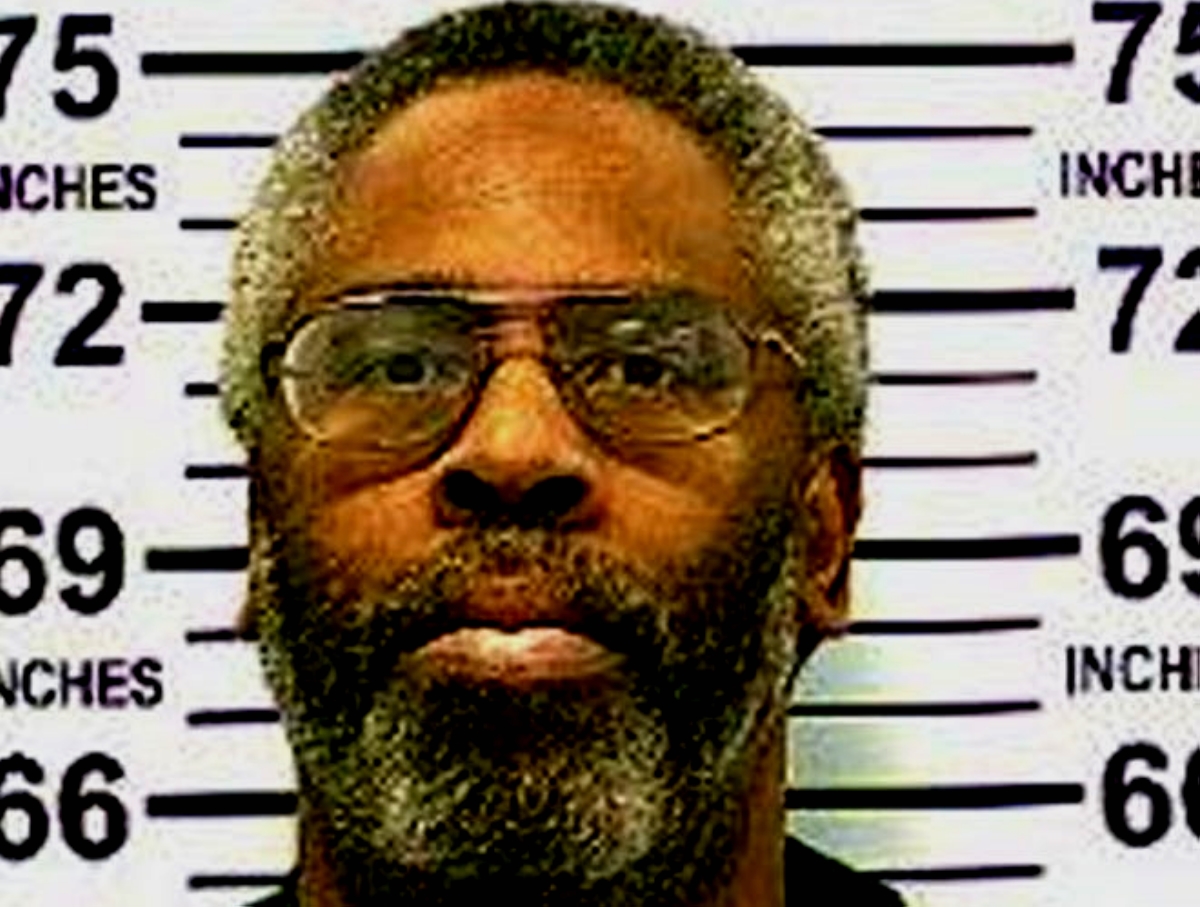

Aside from his odor, Francois' prominent feature was needing two chairs. He was six foot four inches in prison and weighed over three hundred pounds. The heaviest the newspapers logged him as was three hundred and forty. People are almost impressed he could manage his kill count while burdened with that immensity. A high BMI does not disqualify one from all activities, including serial murder. You can gain a sort of invisibility when you exceed what is perceived as normal. His weight was, most notably, his murder weapon.

Francois nursed a victim complex. By the time he was fourteen, he had attained his full height and weighed two hundred and fifty pounds. Though there might have been a genetic component to his body odor, he did himself no favors by ignoring personal hygiene.

Physical differences are not moral failings or destiny. These were no excuses for Francois' crimes. People his size or larger, people with body odor, still prosper. Francois reported predictable schoolyard teasing, but he also learned to use his weight productively. He was a star wrestler at Arlington High School, and his bulk and stature were assets on the football field.

He joined the Army after high school, ending up stationed in Honolulu. Owing to his obesity, he was discharged in 1992, according to The Daily News.

He decided he was entitled to murder because of a sense of rejection he chose to foster. He had demonstrated functionality, an ability to belong in society, but he spurned it, not the other way around.

Francois chose one of the popular victims of serial killers: sex workers. Researchers term some victims the "less dead," meaning that society does not care much when they are murdered. If a bubbly, blonde, cis, straight white teenager from a well-to-do family goes missing, she will be on the front page of international newspapers. When ten Indigenous, plain, fifty-year-old, trans, impoverished sex workers are found in pieces, it barely ranks mentioning. His victims were all white -- though the police investigated him without success for a cold case where the victim was a Black woman -- but they were otherwise the less dead.

The police had repeatedly responded to calls of half-naked women escaping his house and screaming for neighbors to save them. Officers would arrest and release him, treating him as another domestic abuser in their jurisdiction. Even when women went missing around his house, officials seemed disinclined to connect the dots. According to reporter Claudia Rowe, who lived in Poughkeepsie at the time and wrote the book The Spider and the Fly about her lengthy correspondence with Francois, Lt. Bill Siegrist and Detective Skip Mannain put in a half-hearted effort. After arresting Francois, the best they could say was that he had passed a lie detector on January 18, 1998. According to the American Psychological Association, these tests are notoriously unreliable and usually inadmissible in court.

Francois claimed a woman, Wendy Meyers, gave him HIV in 2015. A year later, in October 1996, he choked her unconscious, then drowned her in his bathtub before bringing her body to the attic. He assumed she intended to rip him off by not letting him orgasm, though his only reason was that she asked if he couldn't hurry up.

Meyers' boyfriend reported her missing two days later.

Rather than Meyers' murder giving Francois pause, it whetted his appetite. A month later, he killed Gina Barone, fearing she too might take his money without bringing him to climax, as she had complained he was too heavy and was not finishing promptly. She hurt his pride -- though what she said could not have come as a surprise -- so he choked her to death to finish in peace. He put her body next to Meyers' in the attic.

Two days later, after dropping his mother off at work, he picked up Cathy Marsh and repeated the cycle, taking her to the garage, choking her, washing the body, and storing her in the attic.

After Marsh went missing, local sex workers told the police that Francois liked to choke them. One claimed that Francois pulled back from strangling her, saying, "Oh no. I almost did it again." This information did not affect the investigation enough.

Two and a half months later, after Kathleen Hurley went missing, Siegrist started to suspect the missing women had fallen prey to the same killer.

Francois did not seem bothered by the police. An hour after speaking to them in February, he picked up Mary Healey Giaccone and reenacted his crime.

The first story about the missing women did not appear in papers until December 14, 1997.

Even when he attempted to murder Lora Gallagher, and she filed assault charges against him, he only received a 15-day sentence and served half. Before his arrest for murder, despite the police responding to his having abused women, this was the only incarceration he saw.

Less than a month after his release, he murdered Sandra Jean French, whom he left in his Mickey Mouse comforter while he went to class.

Two months after that, he killed Audrey Pugliese. The 34-year-old only had a few minor arrests, none related to sex work.

Less than two weeks later, he murdered his final victim, Catalina Newmaster. Police had arrested Newmaster a dozen times for crimes relating to her crack addiction and the sex work she did to support it. The police offered her leniency in exchange for wearing a wire, telling her not to get in Francois' car. She wore a wire for them repeatedly, but the police had always pulled her out and ignored her evidence. She even identified him in court during another of his appearances for assault, saying, "That's the killer." This was not good enough, and she would pay with her life for trying to help.

According to The New York Times, Newmaster wasn't the only sex worker with whom the police had this arrangement, nor the only to state that Francois was the killer. Siegrist defended, "All the complaints that came to us were handled in a proper manner and we have done everything we can to solve this crime. [...] These women were human beings and should be treated with as much respect as any other person."

Grady stated that the testimony of these women wasn't enough. "But just because incidents took place doesn't mean arrests can happen. You need probable cause, sufficient evidence."

Had the police better weighed the repeated testimony of the sex workers -- who showed bruises from Francois's hands around their necks -- some of these women might not have been his victims.

The murders stopped only thanks to Christine Sala, whom Francois had tried to attack in his garage. Fortunately, Kierstyn popped her head in and said she needed the car, which stopped Kendall long enough for Sala to escape. She made it to a gas station and called the police.

Francois told Rowe that he had hoped to marry Sala and start a family. However, Francois said to the prosecutor in his case, "Killing seemed easier than getting into a relationship."

The New York Times reported that, in court, Sala, who had gotten off drugs, said, "I hope you remember me for the rest of your life. I hope you remember who put you away. You will never be forgiven for what you have done. I hope they kill you in prison."

Francois did not speak in court, though his lawyer assured that he was "deeply sorry for his action" but did not want to talk in case it could be misconstrued. Given what he said afterward, he may have feared it more being accurately construed.

Mannain told Rowe that he was frustrated that he was pulled away from handing out flyers about Newmaster to respond again to a woman Francois had assaulted. Even though everything about the crime -- the car, the culprit, the fingerprints on Sala's neck -- matched what Newmaster reported, the police still didn't add it up.

This would not be the only time Mannain and Francois crossed paths. During a previous investigation into his serial assaults, Francois invited the detective to his bedroom. Mannain did not report anything unusual, somehow missing the stink of decay above his head, a memory that delighted Francois as he recollected it to Rowe.

When police brought Francois in for assaulting Sala, he said, "I want to talk to the chief prosecutor of the missing women," and confessed everything. So intense were the details that the prosecutor, Margie Smith, collapsed into sobs upon leaving the interrogation room. To Rowe, Francois said, "I could have kept going, it would have gone on and gone on, and they never would have found a thing."

Siegrist said, "For two years, we were hunting a ghost. Nobody really knew what happened to these women. We had no crime scene, no bodies, no nothing -- until the day we arrested Francois" on September 2, 1998.

That night, the police pulled over my friend Audrey for the crime of driving in the same car Francois had.

The police charged Francois with eight counts of first-degree murder, eight counts of second-degree murder, and one count of attempted assault -- though there does not seem to be much "attempted" about Sala's assault.

The police found the bodies stuffed in crawlspaces and kiddy pools, left to rot. His father, McKinley, spent hours every night hanging out within feet of the bodies and was never any the wiser. The detail of the open kiddy pools -- where The Daily News reported he put their skulls -- is too gruesome and improbable. Nothing else suggests he cared about the bodies once he had hidden them, surely not enough to dismember them.

At his sentencing hearing, Francois was indifferent to the statements the victims' families read. This was an improvement over outright laughing at them, as he had done during earlier appearances, The New York Times reported. (His lawyer, Randolph F. Treece, said this was not "sarcastic or sardonic" laughter but merely nervousness.)

Patricia Barone, the mother of victim Gina Barone, did not blame Poughkeepsie -- the city or the police department -- for what happened to her daughter, saying, "How can you blame the city when his own parents didn't know what was going on?"

Francois scored a zero on the Macdonald Triad, which supposedly predicts a child may have serially violent tendencies. There is no evidence he tortured animals, set fires, or wet his bed past early childhood. According to a Radford University report, Francois had no record of drug or alcohol abuse, and he never spent time in a psychiatric center. With serial killers, there are often predictable traumas: one or more severe blows to the head; physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse; parental neglect, or maltreatment. None of these were reported with Francois. The observer may speculate at the point where the rejection of being a colossal man overlapped with his acquiring HIV.

This is not to say he did not have regrets, but none of these were about his victims. Casey Jordan, a criminologist and lawyer who had corresponded with the killer for three years, was quoted in the Poughkeepsie Journal, "He felt no guilt, no remorse, about killing them. [...] He wanted to blame everybody. Once, when I asked him what he did wrong, he said, 'Well, what I did wrong was confess. I should have never confessed. If I had not confessed, they never would have been able to pin it on me.'"

He was no more sympathetic when faced with Marguerite Marsh, the mother of his victim, Catherine Anne Marsh, who visited him in 2008 and said, "He didn't really say that he was sorry for what he had done. [...] [T]hat was the most disturbing part of the visit. I had hoped he would apologize."

According to Rowe, in letters from prison (which he would end with "God Bless!"), Francois said he was "a measured person in thought" but "rash in action." Perhaps one can make that excuse after the first killing, but once one's house contains multiple bodies, any suggestion these were crimes of passion and not intent is insulting.

He stated that he felt all the women he murdered needed to die. He did not feel he had to be the one to do it as long as someone did. Calling him a missionary killer might be giving him too much credit, though. He killed not because he wanted to rid the world of the plague of sex workers but because he was sexually frustrated.

Once the women were dead and hidden away, he had no interest in their bodies. He was a process, not a product, killer. If the women blipped out of existence after he choked them to death, he would only have been too happy.

According to the Poughkeepsie Journal. Francois maintained that he didn't remember his crimes, only how he felt, writing, "Even those feelings may only be a justification after the fact for what I did."

According to Cornell University, his attempt to plead guilty to avoid capital punishment was not without complications. Only a jury is authorized to recommend the death penalty. He wanted to circumvent standing before one, suspecting no one would view his crimes leniently. The New York Times reported that Judge Thomas J. Dolan of County Court believed that a death penalty trial would serve "no good purpose." Dolan instead sentenced him to eight consecutive life terms without a chance of parole. The district attorney was none too pleased by this plea, according to The New York Times.

His lack of a death sentence was a relief to some of the victims' families, who did not want to endure the more protracted legal battle.

Some, such as Rowe, found the killer's brutality "tantaliz[ing]." It is unclear in her book if this would be the case for any killer on whom she had centered a book or if Francois held some morbid charm invisible to most. Given that, on visiting him in prison, her heart "pounded the way it had with boys in high school," so flattered was she by his interest in her, she may not be the most objective reporter. Rowe is not unusual in the world of true crime, someone who enjoys the by-proxy excitement of being near something horrifying but rendered inert. The Spider and the Fly details how she resembles his victims; like her book, the resemblance is only superficial. Even when interviewing sex workers whom Francois had sexually and physically assaulted, she equates the women's forthrightness as being "like children at a candy buffet." Though she is willing to render his victims and locals she interviewed into caricature, she "enjoyed thinking of Kendall as complex and independent," all evidence to the contrary. Then again, as Annalisa Quinn notes in an NPR book review, Rowe "enters into a world of pain and violence and comes away only with a book about herself."

A gory, faux documentary titled The Poughkeepsie Tapes came out years later. Some thought it was based on this case, which gives Francois too much credit by far. Unlike the killer in the movie, Francois operated for only a couple of years. He made no videotapes of the murders -- that would require too much planning. Francois was not some insidious ghoul. He was an opportunistic loser whose only hobby outside Magic seemed to be murdering innocent women. He doesn't deserve to be a cinematic monster. You cannot summon Francois by saying his name in a mirror. He won't follow you with a chainsaw. He didn't have an altar of bones and body parts. You would not flee screaming to see him or struggle to outrun him. Unless he had his weight on you in the back of his car, unless you were close enough to strangle, he would do nothing but sexually harass you. He did not use guns or knives, even in disposing of the bodies. He was assumed to be intellectually at the barely average level, not some cunning tactician. He had no acerbic quips for the viewer.

The aftershocks of this murder did not abate. The families of his victims are still in the area. I worked with James DeSalvo, an upbeat author and a teacher at Poughkeepsie High School, and the brother of Kathy Hurley, one of Francois' victims. We had crossed paths a hundred times before someone brought up Francois, and DeSalvo mentioned his connection. It is a pain few could imagine, not only to have one's sibling murdered but to become some tangential part of a misunderstood crime. The only solace might be that Francois was caught and incarcerated, so amateur detectives will not harass him to be the ones to solve the case.

Francois was housed for years at Attica Correctional Facility on a block reserved for well-behaved inmates, where he received special privileges. Still, he did not enjoy his visits outside the prison, stating to Rowe that seeing the countryside was "a pale reminder of what I've given up."

He lived for a month at Wende Correctional Facility's Regional Medical Unit. He died at forty-three of a cancerous mass in his groin.

The house is still there, far better cared for. A woman who lived at 99 Fulton after the murders insisted that it is not haunted. At least, the victims do not haunt it.

Thomm Quackenbush is an author and teacher in the Hudson Valley. He has published four novels in his Night's Dream series (We Shadows, Danse Macabre, Artificial Gods, and Flies to Wanton Boys). He has sold jewelry in Victorian England, confused children as a mad scientist, filed away more books than anyone has ever read, and tried to inspire the learning disabled, gifted, and adjudicated. He can cross one eye, raise one eyebrow, and once accidentally groped a ghost. When not writing, he can be found biking, hiking the Adirondacks, grazing on snacks at art openings, and keeping a straight face when listening to people tell him they are in touch with 164 species of interstellar beings.