"Where is my baby?"

Her cheeks were bloodless tatters. Where her eyes should have been, Zed saw only sockets. Her legs ended a half meter from the ground in ragged flesh.

"No babies here." Zed pointed in the opposite direction from where he meant to go. "Try down the road a little, Cynthia."

She floated away. She would ask again when next Zed came by this way. He wished she were capable of being bored asking him for a baby that hadn't existed for tens of thousands of years. She wasn't a Repeater, merely stuck, not fully Awake.

When he turned around, she had already faded.

The sun was low, red on the horizon, enormous. Ghosts appeared from dusk to dawn, though there was no reason for it. They were as dead, as prone to haunting now as any other time. They simply didn't. Scientists--not parapsychologists or psychics as it used to be, but proper scientists who understood a verifiable, repeatable experiment when they saw one--suggested long ago this had to do with the sunlight itself. The solar radiation energized the particles that clung to this earthly realm. When the sun set, something led them to roam as though to find another source of energy.

He didn't care for the idea, as though it were all about feeding. Still, he couldn't contest that these between-times brought them out. The sun went below the horizon, and the dead rose. The sun found the ground afresh, and the dead faded. If there were clocks, one could have set them to the preciseness of transition.

He raised his hand to the sky, but it did no good. The waning light poured through his fingers. He could see it with his eyes closed, though closing them was only an affectation now.

The sun set enough that a few stars peeped out, though the sky was not dark. The sky never turned less than dim. You could still read a book by the light, though he could not recall the last time he had seen a book.

He looked down the hill, the spirits gathering in the cracked streets like a noxious fog. Some of them had shapes he could make out, human but with missing or faded limbs. A few were almost solid enough to be believed living people, but that was impossible.

Few of the dead were much for conversation. They would repeat questions or actions, what their life had left of them. They were recordings in building centuries rubble. The air above filled so thickly with ghosts that one could see where the floors had once been.

He hated the screaming the most, having no way to block it out. He always woke to screaming. A little was from murders, the last agonized air force from punctured lungs.

The rest was worse. Tens of thousands of people mindlessly sobbing over their dead parents and children or their deaths eons ago. Murder was one moment in time. Sobbing was forever.

Those who were intelligent, the Awake, gathered far from cities, away from the moaning. They left where they appeared because they could, because it made them different from the rest.

Zed did not know what he looked like, though others had told him. There was nothing in him that could be reflected, and little in the world to do the reflecting, water most of all. The dead used one another as mirrors, having their faces described. He knew details, though there was no force of opinion behind them, no judgment of beauty or ugliness. As did many of his era, he had copper skin and a light brown beard. His eyes were deep-set, his nose was broad. He materialized nightly in a tunic and black pants.

He didn't know if this was how he looked in life or if he had become this way since. Memories from then were hazy enough to be useless, a commonplace malady.

If he had once had a family -- everyone did on some level -- it had been too long ago to recall. He decided his name was Ezekiel, which he abbreviated to Zed, but he didn't know if this was true or something he had picked up. It didn't matter. There was no reason or ability to contradict this nominative decision.

As far as Zed understood it, he had unfinished business, though he couldn't recollect what it would have been. He was dead. He knew that. In so much company, it seemed rude to dwell.

There was no one to haunt into acting on his behalf, no one to bury his remains. He doubted anything of him existed, having been recycled through the guts of worms. He had no purpose on the Earth, but he remained. Maybe, he thought, no one ever has a purpose but went on pretending they did to ease the panic.

Some of the cursed dead remembered how they had died, which gave them insight into what they might need to do to move on.

Moving on seemed like disappearing, and there could be no catharsis. His soul was not unquiet or trapped, but everything remaining on the planet was trapped. The world was set to end one of these nights, and he saw nothing after.

There was no communication over distances, so some believed they existed in the sole necropolis on Earth, every ghost together and none natives. It did not feel true. He could not go far enough every night to prove his feelings right.

Willingly vanishing was tempting oblivion. There was no guarantee one would reappear. Close, within a hundred known kilometers, was possible but not recommended.

There were no animals, which he missed. There were few things he found more relaxing than the charming stupidity of squirrels.

The heat was too much for most life, though he didn't feel it. He understood heat on a curious level. He could lay his spectral hand on a rock and know it was hot enough to burn, but he could not register it. There was no longer anything in him capable of burning.

He wondered at God, in the absence of anything else to do. Zed existed still, which had to mean something more should exist. The world was not filled with nihilists now, just the mindless and confused. The dead could not kill themselves, or most would to avoid another day outside humanity.

He could hold things, especially at dawn and dusk, and built cairns on hilltops. They meant nothing, but they occupied him. Eternity was nothing if it was not dull.

Other ghosts watched him lift the rocks, stone by stone by stone, until he had given shape to what was formless. The audience once bothered him, but they must have been as bored as he was. He lifted the rocks, and they did not.

The world had already ended. Ghosts couldn't reproduce. Few were sensible or stayed that way long. They could not change or grow. They faded, but it was impossible to know if that was another death. When fire ate the world, Zed would end, but his death was so long in the past that it didn't bear discussion. He was something, but it was not alive.

He didn't know how long ago the living left them behind. He remembered them going, but night didn't follow day for the dead. Long enough that artifacts were rare and infrequently whole, that buildings were largely notional.

There wasn't sex among the dead. It wasn't that they couldn't touch as that it felt like nothing. Not pain, not pleasure. For the Awake, passing through solid objects was irritating, but that was as far as even discomfort went.

Zed could feel for others of the dead. He cared about the Awake. He wanted to see them. They couldn't tell when one of them left, if they would ever see them again, if they would be gone for an hour or a hundred years or forever. It made every parting somber, but they became honest for it. They meant every goodbye in a way they couldn't in life.

Some of the Awake tried to form bodies of dust and detritus. It wasn't corporeality and wreaked havoc on their tangibility, but it was how they reacted to the end of the world, by pretending. He couldn't blame them.

They gathered under the moonlight, almost day for how bright the moon had become. By talking, they thought they could resolve what was left unfinished. It was group therapy to quit guilt for sins whose recipients were long dead. They were the only ones who remembered.

"I'm so sorry for any pain I caused you," said Renee, the shade of a thin woman in a flowing red dress. "Had I known that it would have been the last time I would ever see you, I would have told you of my love for you and welcomed your proposal."

"I knew you did. I forgive you," said a spirit Zed did not know, a man with a bushy mustache and beady black eyes.

If they breathed, it could be said they held their breath for some change to have been catalyzed. None came as none ever did.

The new ghost did not know Renee before this. All night, one could watch these improvised plays, these confessions and admissions. Among the Awake, this bordered on a sport. The believers turned actors, the cynics, the critical audience.

Some of the dead played at affectations such as keeping house and going through the motions of preparing and eating imaginary food. These were not Repeaters but the sentient who wanted the comfort of the familiar.

Zed despised this. Being dead here was unfortunate. If he forgot this status for even a moment, this was beyond Hell. Better to suffer numbness than agony.

Sara came up beside him, surprising him. The dead did not make any noise, even to members of their species. She was a slight girl, looking ten years old, but acted a hundred. "The world ended once, Zed. Wasn't that enough for you?"

He had told her how he expected this to end. She hadn't believed him then, a decade ago. He considered the argument settled. She brought it up every time she happened upon him, as though he were still arguing.

"If you were right," she said, her tone suggesting that only a fool would be right about this, "we would have nowhere to haunt. Why believe in that?"

"What is the point of haunting? Who are we haunting anymore?"

"Does haunting have a purpose? Are were still alive" -- she caught herself -- "around because something wants us to be? We just are. No reason. No gods or devils. We are here because we are something that occasionally happens in the universe, and we have not finished happening."

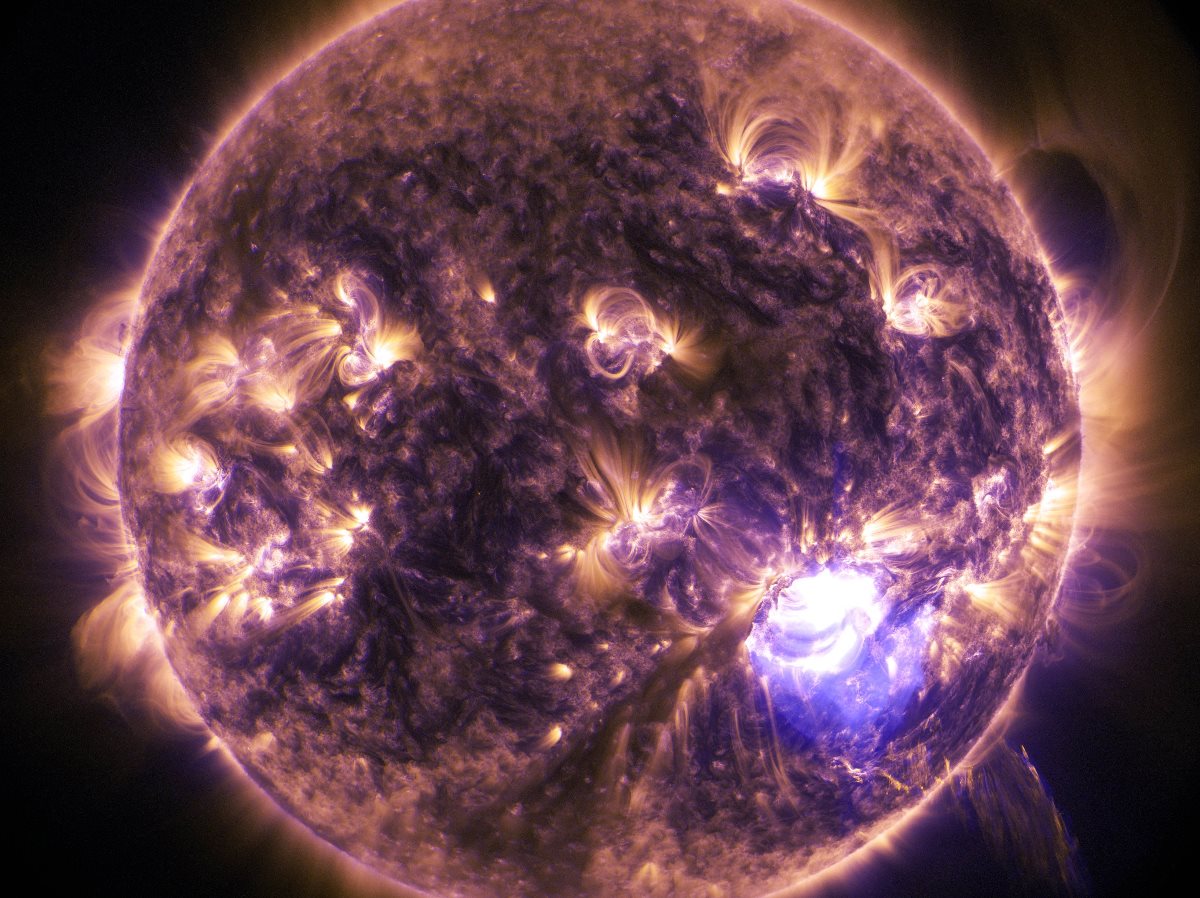

"When the sun goes nova, it will swallow the earth," he said, renewing the argument to occupy himself. "It will be a cinder. Will we still be here, unfinished? No. We will cease being."

"I think we will vanish."

He didn't know if she did think this, that they would be assumed to the heavens for some greater purpose. She would ascend to whatever afterlife came after this one if she was right. If she were wrong, she would never have to know about it.

The sun would destroy him, destroy them all. They couldn't know exactly when, though the prevalence of the dead suggested it would be soon. There was no sense to it, except that even the sun would have to die someday. It did not care if there were minds to mourn it. There would be no ghost of the sun. Its business was not unfinished. Whatever held them here, their bones or land or treasured objects, would be atomized in this crucible. That must result in a final extinction.

Among the dead, the strongest arguments were over what could happen next. For the miracle of his existence after death, he held with nothingness. He would exist, then he would not. There was little else to say.

Others clung to the familiar for comfort. God was surely not cruel, not after untold years since the Old Testament, and would consider their tenure on a forgotten world as penance enough for any mortal sins. When His finest Creation ceased, they would all be translated to Heaven, believers and doubters alike.

Others expected to leave this karmic cycle with the purification of the celestial fire. Or their souls were in a holding pattern until there were enough creatures on a new world for their reincarnation. Those who vanished were not to be mourned but envied. They were now cows and frogs under twin moons or beneath glowing rings.

This last point stuck in his throat. He remembered the exodus, the uncertain, fretful whispers of the officers. He knew, though he never mentioned, that their ships might drift forever. The living who escaped the Earth might all die on the journey. A hostile planet could undo terraforming in innumerable ways. Even a common cold could mutate into a plague. But a tiny chance in the stars conquered a sure eradication on their homeworld.

The living had no more duty to the dead than to persist. They could not bring the dead with them but in memories and stories -- keepsakes were forbidden because every ounce cost. New worlds would be peopled with fresh ghosts because a death is the only gift promised to every newborn. Earth was only the first of many planets populated wholly by the dead for all he knew.

Some argued the ghosts remained here only because the memories of surviving people still held them. Zed found this arrogant and sentimental. He was forgotten here a thousand times over.

Some living people lingered after the ships left. Their religion condemned abandoning the planet, though the planet had condemned them. Others stayed to be certain that most people would escape, impossible to guarantee without human hands on the ground.

There were machines, shaped like humans, that wandered until a part went bad, and they sputtered to uselessness. Mindless ghosts pursued them, begging for intervention, for their missing babies, or for rides to the cemeteries where they were buried. Back then, the machines could not see the ghosts. Once the sun became its deep red color and the dead were more robust, there were no longer androids to pester.

Zed couldn't be sure, but he didn't warrant he'd met a ghost made in the last ten thousand years. People died in the evacuation of the Earth, as panic set in. When there was news, the news put the death toll in the billions. This was a tragedy, but people admitted it was for the best behind closed doors when they assumed no one else was there to hear. Fewer people made the evacuation easier and let the supplies on the ships last. Sacrifices needed to be made. Wasn't it better that humanity ascend with cleaner hands?

He had died a century before any of this happened. He didn't manifest between the time of his death and the beginning of the evacuation. He thought that this was what he needed to hear, that his purpose was to help or hinder this end of days.

That apocalypse came and went.

A notion came to Zed that night. He did not want to build another cairn. He did not decide to do this now because he intended it to mean something, but only as an excuse not to watch another melodrama with an impossible conclusion.

Dead babies were in short supply. While babies were nothing but unfinished business, having had the potential of their eight or so decades stripped from them, they did not have the wherewithal to mind as they expired.

Short supply, but they did exist, having been murdered or cried themselves to death from exposure or starvation. Zed asked around until someone mentioned the cries of a baby kilometers away.

The travel was not hard, bereft fatigue. He knew the land the ghost had mentioned, having passed through there thousands of times on his wandering. Zed hated vanishing, unsure whether he would reappear, but he did so now. Otherwise, he might have wasted this night.

The cries were easy to distinguish from the moaning around her. The baby's wailing carried on the catastrophic wind. Her crying stopped in a solitary, curious gurgle when he lifted her from the parched ground. How long had it been since anyone had tried to hold her? Would another member of the dead have thought to?

He could have vanished to find Cynthia, but he had no certainty that the baby would transport with him. He had not had cause to walk far in a century, but he walked now, this weightless starved child in his arms only feigning sleep because the dead are a sleepless race. They disappeared in the morning, but it was not filled with memories, rest, or dreams. Other ghosts, the Awake and otherwise, saw him with the baby, but they could not reconcile the meaning. This was strange, but it was not their business.

Before dawn, he came back to the land where he appeared every night. Having spent untold time trying to avoid Cynthia, it was no struggle to find her now.

"My baby! Where is my baby?"

Zed held the ephemeral infant out as though her diaper needed changing.

Cynthia stopped her moaning inquiries after seconds more, too used to reiterating her misery for eternity.

"My baby?" she asked, more like a woman than he had ever seen her. Her legs, still insubstantial, faded into sight beneath the gore of her knees. She blinked her eyes, brown and watering.

"A baby who needs a mother," Zed corrected. "As good as yours."

She opened her arms to receive this parcel. It only occurred to him now to wonder if she was substantial enough to hold anything, even this whisper of a child. Though he could lift rocks and had no struggle to cradle the baby to his chest, Cynthia had never had cause to touch anything.

No more harm could come to the baby than would when the sun swallowed them, so he tenderly placed the baby in her arms until he felt the resistance of imagined substance.

The baby pretended to wake now, her eyes enormous emeralds, the most solid part of her. Cynthia clutched her baby to her breast, murmuring "My baby" once more. She shined like morning, the baby brighter still.

She was not there when Zed appeared in the evening.

He did not think he would see her again.

Thomm Quackenbush is an author and teacher in the Hudson Valley. He has published four novels in his Night's Dream series (We Shadows, Danse Macabre, Artificial Gods, and Flies to Wanton Boys). He has sold jewelry in Victorian England, confused children as a mad scientist, filed away more books than anyone has ever read, and tried to inspire the learning disabled, gifted, and adjudicated. He can cross one eye, raise one eyebrow, and once accidentally groped a ghost. When not writing, he can be found biking, hiking the Adirondacks, grazing on snacks at art openings, and keeping a straight face when listening to people tell him they are in touch with 164 species of interstellar beings.